Checkouts of works in translation by 3 recent Booker International winners from the Seattle Public Library across different media.

Welcome to my Google Data Analytics Certificate Case Study capstone project.

Contents

- Business Task & Context

- Data Sources

- Data Format

- Cleaning and Manipulation of Data

- Summary of my Analysis

- Supporting Visualizations

- Further exploration

- High-level insights: literature translated into English

Business Task & Context

A local library without very much translated fiction would like to include more new international translated fiction in its offerings, but has a limited budget. Translated fiction can be expensive and difficult to acquire from the usual sources, and often requires librarians with discretionary budgets to go “into the wild” to source from independent publishers overseas, or wait several months for it to become available in the U.S.. Sometimes ebooks can be acquired more readily and cheaply, or patrons request audiobooks. Therefore, it’s important to know which formats most appeal to readers.

The Generation TF: who is really reading translated fiction in the UK article on the Booker website shows trends of translated fiction book purchasers in the U.K., and that data also shows that buyers prefer physical volumes as opposed to ebooks: “The TF buyer is less likely to prefer ebooks to printed books than the overall fiction buyer (14% vs 30%).”

On the other hand, the industry standard Nielsen Report data in the 2021 article: “Nielsen survey finds digital formats booming in record year for book sales” notes that ebook interest has been on the rise.

The library would like a study which more accurately reflects their patronage: library borrowers rather than purchasers, more locally in the United States and Pacific Northwest specifically.

In this hypothetical, the library acquisitions department wants to know: Do patrons more often check out translated international fiction in book form, ebook form, or audiobook form? Which is the best to invest in more of? Has this changed over the last 5 years or so, and if so, how?

One key data source used will be open source historical checkout data of international translated fiction from another nearby library.

Data Sources

Open-source book sales data is notoriously hard to get ahold of (see Where is all the Book Data), and that which is available can become rapidly out of date.

The Seattle Public Library open sources its book checkout data from 2005 to the present. This data is useful because it a) reflects checkouts of library borrowers rather than purchasers, and b) is in the same geographic region as the library requesting the study. It’s also from a trustworthy source, provided directly by the institution.

“This dataset includes a monthly count of Seattle Public Library checkouts by title for physical and electronic items. The dataset begins with checkouts that occurred in April 2005. Updated April 21, 2023. Data Provided by The Seattle Public Library”

The second data set I used was simply a list of the authors of the books which won the International Booker Prize in 2018, 2019, and 2020 respectively. I wanted to choose authors who had won more recently so their books would theoretically be in high demand, with enough time between their win and the present day to show trends over the last 2-4 years of checkout data.

Data Format

It makes sense to build bar charts about:

- how many books, ebooks, and audiobooks in sum have been checked out, with

- comparisons across years between 2019 and 2023,

- possibly also faceted by author

- stacked bar charts which demonstrate the rise, fall, or continuation of popularity of each format over time as aggregated from all of the data

- A month-by-month view might demonstrate seasonal trends.

- A view which includes publishers might be informative as a sidebar for sourcing information.

Cleaning and Manipulation of Data

Exploring the Data

Spending some time in the Seattle Public Library checkout data allowed me to find out its strengths and limitations.

One big limitation I encountered right off the bat was that sometimes the column information for the data I wanted could be missing or inconsistent. For example, to get a listing of the translated literature, I had to do a filter search in which the word “translate” was included in the title, because that is where “translated from the Polish” or “translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones” was appended to the title. It wasn’t included in the author area nor did it have its own column. It also wasn’t included in the genre/description information. The genre information seemed extremely inconsistent in general, noting themes like “eccentrics” on some but not all of a work’s description across mediums.

What I soon found, however, was that my search with “translate” in the title did not return any ebooks or audiobooks. Why? At first I wondered if the library didn’t stock these, so I consulted the current library catalog and found that there were several ebooks and audiobooks available for each title. I searched by book title in the database instead, and did find ebook listings. It seems that ebooks or audiobooks simply did not have any indication of whether a book had been translated or not anywhere in their listings (title, author, or description fields). When I looked in the live library catalog, I could see that the translator was sometimes listed on ebooks or audiobooks as a “collaborator,” a category field which did not show up in the open source data.

This limited the data I could easily get about translated literature in general with regard to format, and it was impossible to parse something like “fiction” or “prizewinning” out of the description which just noted: “eccentrics.”

When I conducted an author name search, however, I was able to see extensive data about formats. The name search for the English name even returned results for one author’s name spelled in her native Arabic. What I deduced was that I would need an additional data source for author names in order to get the more specific information I wanted.

This led me to select a few authors from the International Booker Prize, given that these authors were as a result of the prize fairly popular and of potential interest to libraries in general. Next I compiled the library data for each chosen author onto a Google spreadsheet, where I could append the downloaded csv file for each author to the same file. This was possible to use Google Sheets for because there wasn’t an overwhelming amount of data. I also considered using the Nobel Prize in Literature, but to keep this project extensible I chose the Booker because of the ability to “go broader or deeper” on this project at a later point by adding data for the shortlisted or longlisted authors in a given year. Additionally, most of the International Booker winners wrote in languages other than English; including someone like Bob Dylan or Alice Munro from the Nobel list would have defeated the purpose of looking specifically at literature in translation. Also, admittedly, I don’t personally like Peter Handke and was much more excited about the International Booker winners.

Continuing to cross-check offerings in the live library catalog information served the purpose of touchstone checks on the data integrity for my dataset.

Cleaning and Transforming the Data

Once I had the data for my three authors compiled onto my Google Sheet, I could spend more time working with it. First, I eliminated columns I didn’t need: ISBN number and subject/description. For now, I kept the publisher, checkout month and a few other things.

First I bolded the column headings.

Next, I examined the columns.

Some listings had left the publication year in brackets (ie: [2022]), while the rest of the years did not have brackets. So I needed to use “split column” to separate the years from the brackets in the listings which included brackets.

While the library had returned one author’s name in both Arabic and English, I decided to format it in English for the sake of consistency so completed a find and replace search.

Also, sometimes ebooks or audiobooks listed the author’s first name before the last name, and some of the books listed things like the author’s year of birth or additional names, so I also needed to standardize the names, again using find and replace.

The authors’ names were thankfully all unique enough that there was only one case of there being an additional author with the Tokarczuk surname. Had this project been any larger or with more commonplace names, more cleanup of this kind would have been required. For example, splitting columns by first and last name, and finding any which didn’t include the correct first name. If one of the authors had had a very common first and last name, which would have returned a large number of irrelevant results, this task might have become quite complicated.

Additionally, I noticed that I had also ended up with listings of books by the authors which were in their original languages, or had been translated into languages other than English. While this adds a very interesting dimension, in order to keep the data consistent in terms of literature translated into English, I removed these listings.

There were additional small items to clean up (ie ‘Abridged’ vs ‘abridged’) where inconsistent labeling led to multiple data points for a single type of media per title per year, so I made these more consistent to the extent that it was relevant to the data that I wanted to use.

As I worked with the data to build charts, I discovered additional aspects that needed to be cleaned up and had to refresh my data source with the corrected spreadsheet. This shows that there may still be aspects about the data – especially bigger data – that don’t emerge until one begins to manipulate it, and reminded me to build time into future projects for dry runs to identify additional areas that may need to be cleaned.

I used the SUM function to find out how many total checkouts I was looking at: 11,018

I used the COUNTUNIQUE function to verify that I only had 3 formats included: books, ebooks, and audiobooks.

I used COUNTIF to count the totals of each: =COUNTIF(C2:C700, “BOOK”) to find out approximately how many months of each media appeared in the number of checkouts (255 books, 239 ebooks, and 155 audiobooks). It emerged that the library did not stock any audiobooks of a book by Rijneveld, while it did stock audiobooks for almost all other books, which could well account for the lower number of audiobooks.

I also used COUNTUNIQUE to find the total number of titles (the same work often had different title variations across different media), 22. Among the three authors, there are 9 total books: 1 by Rijneveld, 2 by Alharthi, and 6 by Tokarczuk. Of those, House of Day, House of Night (Tokarczuk) was available only in book form, Primeval and Other Times (Tokarczuk) was available only in ebook form, and The Discomfort of Evening (Rijneveld) was available in both book and ebook format, but not audiobook. I decided to keep the books which were only available in one or two formats for the time being, flagging this as a place where I might eliminate those listings altogether in the future to tidy up the data more.

The next choice was which program to use to analyze and visualize the data.

Though I had hoped to work in R, I didn’t have a ton of complex calculations or additional manipulations that needed to be done, there simply wasn’t enough data to justify using R as opposed to the more expedient route of working in Tableau. Also I wanted to make sure my results were open source by default. Therefore I decided to use Tableau.

Summary of my Analysis

My analysis shows that:

- checkouts of ebooks have grown significantly since 2019,

- audiobook rental has generally held steady

- more recently, there are roughly equal checkouts of ebooks, physical books and audiobooks especially in 2022 and the Q1 data of 2023.

- Additionally, during the summer months, patrons steadily borrow ebooks even while they don’t borrow as many physical books, the rentals of which surge again during the winter months in the Pacific Northwest.

- Including additional authors could be useful in terms of balancing out for differences of prolific publication, popularity, accessibility

Supporting Visualizations

Seattle Public Library data on checkout mediums of 3 recent Booker International translated fiction winners: (in Tableau)

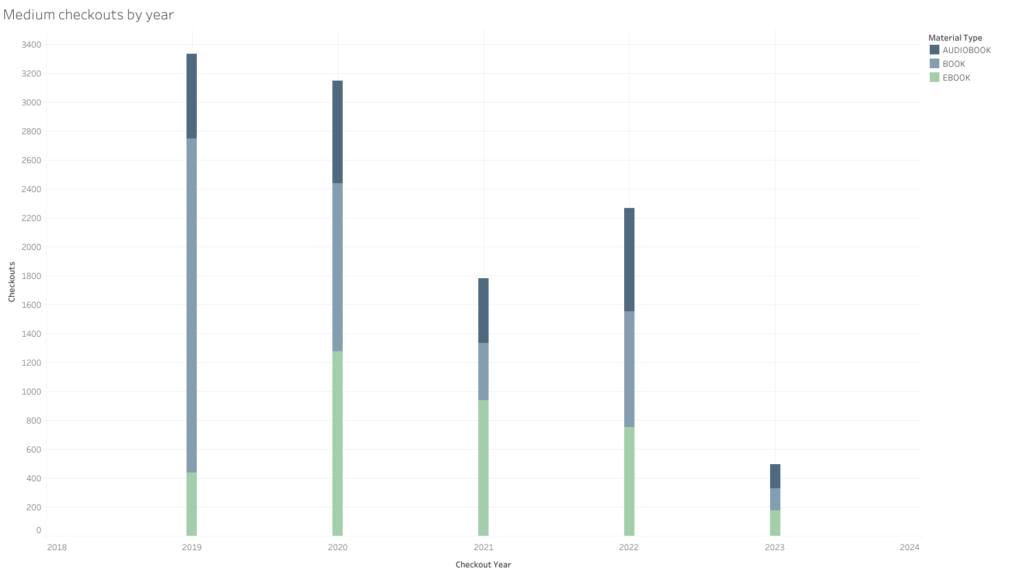

For a number of possible reasons such as covid-19 library closures, the rental of ebooks rose significantly during the years of 2020 and 2021. The 2020 book format rentals were almost half those of the 2019 numbers, while ebook rentals nearly tripled. There was a reduction in all rentals from 2020 through 2021, but the biggest reductions were in physical books. The audiobook rentals had less dramatic although notable changes. In 2022 and in the 2023 data (available only for a little more than Q1 of 2023) show a nearly even 3-way split among the three mediums, with ebook rentals still almost double the 2019 levels.

Checkouts of different mediums by month across all years: (in Tableau)

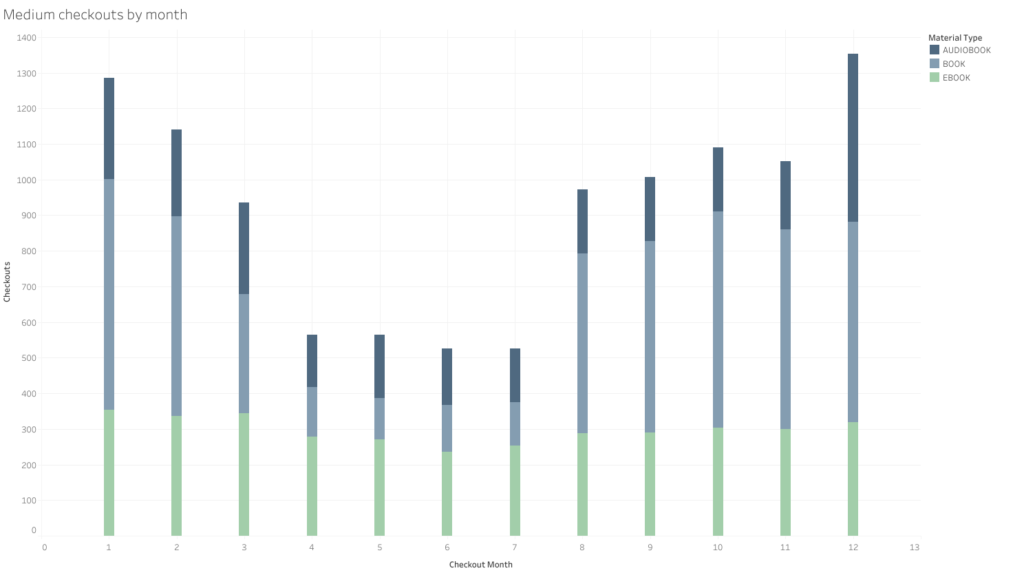

Really interesting and surprising! I nearly didn’t perform this analysis, but am so glad I did because it’s full of rich information. During the summer months, the checkout numbers of ebooks remain pretty solid with only a slight decrease, while checkouts of physical books sharply decline over the Pacific Northwest summer months. Possible reasons for this may be that people are simply traveling more and traveling lightly. Or, fewer books that may be included in literature curriculum in high school or college classes are being checked out. Similarly, audiobook checkouts also decline in the summer but by much less than physical books. However, audiobooks seem to surge around the winter holidays (maybe something to listen to while baking or gathering with family? Dylan Thomas?).

Checkouts by author (alphabetically) (in Tableau)

Booker International Winners:

Olga Tokarczuk (2019), Jokha Alahari (2020), Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (2021)

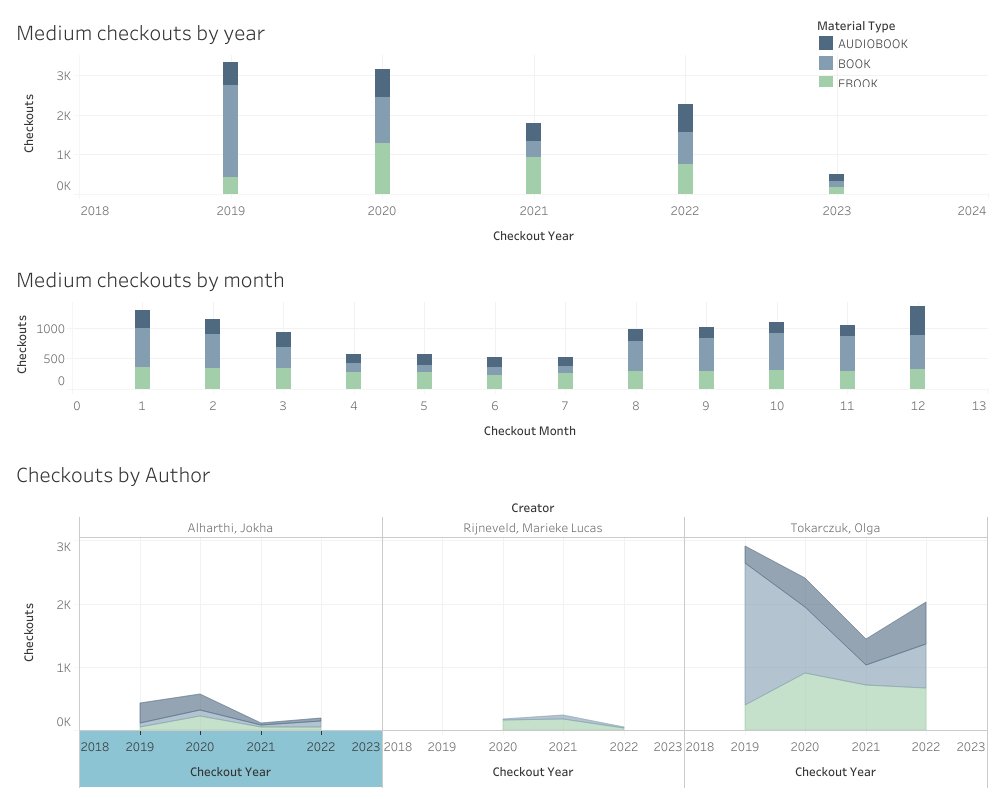

There are all kinds of things going on here. Each author shows a spike especially in ebook rentals in the year of her/their award (a Booker bounce). What needs to be mentioned is that while Olga Tokarczuk has published extensively, the other two have one or two books published only, so register much smaller trends. Additionally, there does not seem to be an audiobook option for Rijneveld’s work. As Tokarzcuk has continued to publish and win prizes, her works continue to be in demand, across all mediums, though book rentals have not nearly returned to 2019 levels, while ebook rentals have generally held their steady gains (it also needs to be mentioned here that Tokarczuk’s most recent novel is close to 1000 pages, which may tilt some into going for the lighter ebook).

This area of analysis seems to reveal flaws in that the dataset may remain problematic in terms of such big differences among authors in terms of prolific publication and popularity; some of the books are more challenging for readers than others. It would be easy at this point for Tokarczuk’s numbers to really skew the entire analysis for any number of external reasons.

For this reason, although this data was based on 11,018 total checkouts, a project like this needs more authors included in order to become more meaningful.

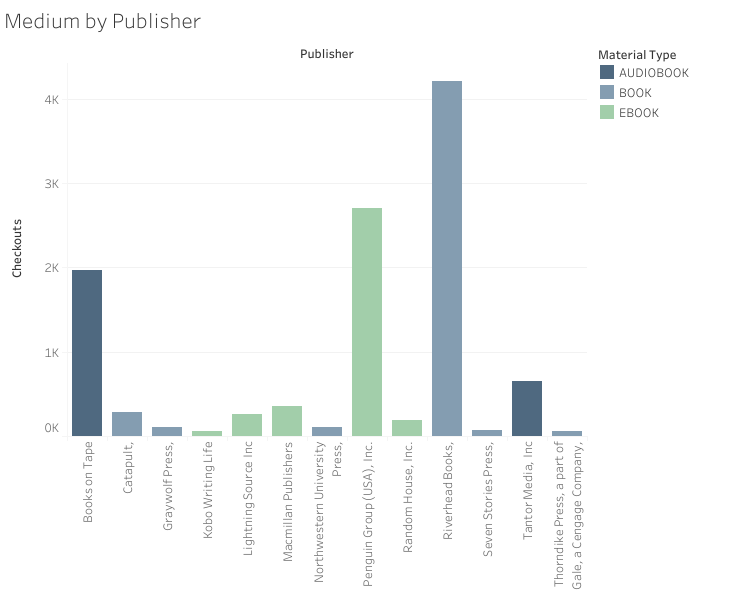

As an aside: medium availability by publisher (in Tableau)

We can see that libraries must source different medium by the same author from several different sources: in fact, no two or more mediums are sourced from the same publisher. This increases the complexity of the library’s task in not only acquiring a variety of mediums, but also in terms of the information that goes into the database about each work. There doesn’t seem to be a consistent standard, based on my earlier data exploration work, and the variety of sources could play a role in this.

Dashboard of all data (in Tableau)

This dashboard consolidates the data. If it were possible to have a current live data stream for the rest of 2023, a dashboard like this would be very helpful in getting up-to-the-month prescient stats to be able to adapt even more quickly to borrowing trends. The legend is floating and applies across all charts. Including the author info helps to show how the data may be skewed by the popularity of a single author.

Further exploration

It would be really useful to include additional authors in this analysis in order to broaden and deepen the dataset and insights.

Additionally, it would be useful to be able to compare the popularity of ebooks and audiobooks for international translated fiction to ebook and audiobook checkouts for other genres or international bestsellers, which would require additional datasets.

The topic of publishers – and who publishes what – is another area that could be pursued, along with the associated costs of purchasing from different publishers.

Further, one could argue for a chicken-and-egg question afoot here: are patrons checking out more ebooks or audiobooks because there are more available, or is demand driving acquisition? For this reason, it would also be interesting to see the library’s acquisition numbers. However, the seasonal information seems to indicate that while physical books are available, they simply aren’t being checked out at the same volume. The seasonal information also suggests that while some people who might be waitlisted for one preferred medium might have opted to check out a different medium which was available sooner, this doesn’t seem to have large impact on the overall trends.

High-level insights: literature translated into English

- At the present rates, libraries in the Pacific Northwest might be wise to source ebooks, audiobooks, and physical books of literature translated into English in roughly equal numbers.

- If libraries need to stagger acquisition times for new acquisitions of literature translated into English, ebooks and audiobooks should be sourced year-round while the majority of physical volumes should be sourced in advance of the autumn/winter months.

- Libraries will need to take into account the necessity of sourcing different mediums from different publishers

- Libraries will need to think about the complexities of naming conventions in adding works of different mediums to their databases for consistency, adding fields to entries to include translators or that books are in translation

- It would be useful for more libraries to open source their data, and also to adopt consistent database conventions across mediums.

- The Booker International and Nobel Prize in Literature are just two starting places for finding popular international fiction; anything from book club book lists to book fair winners to listicles could be fair game here.